A new consensus definition on postbiotics, published by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), aims to clear up ambiguities in the use of the term and provide a framework for academics and industry to continue researching and developing in the area.

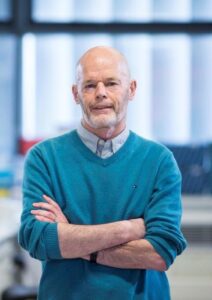

Speaking at a recent Naturally Informed online event, Dr Colin Hill, of APC Microbiome Ireland and University College Cork presented a first look at the ISAPP definition, introducing the new definition and discussing some of the core issues relating to postbiotics.

He noted that the ISAPP consensus paper comes at a time when the term ‘postbiotic’ is increasingly found in the scientific literature and also on commercial products. However, the term is used inconsistently used and lacks a clear definition.

“What we want to do is propose a useful definition and establish a common foundation for future developments,” Hill told attendees, noting that the ISAPP panel made up of multiple independent experts from around the world met up in London in late 2019 to discuss the issue of postbiotics.

According to the new consensus definition, postbiotics are “a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers health benefit on the host.”

Breaking the definition down, Hill said that this essentially means that postbiotics are deliberately inactivated microbial cells or cell components, either with or without their metabolites, that confer a health benefit.

As with definitions of probiotics and prebiotics, the ISAPP consensus on postbiotics states that use of the term must be linked to a health benefit, he added.

“All these terms really only makes sense if they’re linked to a health benefit in the target host,” said Hill, adding that the beneficial effect must be confirmed in the target host in the species and subpopulation.

Postbiotics: Following life

Hill noted that the word ‘preparation’ was used in the definition because it is important to signify the likelihood that it is specific formulation and process to produce the microbial biomass that makes up a postbiotic – and the matrix and inactivation methods ‘are all likely to play a role.’

“We didn’t want it to be that if you could show that a heat-killed liquid preparation of a bacterium had a health benefit that you could then take the same bacterium and dry it and formulate into another food and just simply transfer across the health benefit,” said Hill. “You have to prove the effect for a specific preparation, so the term postbiotic would be reserved for specific preparations.”

Hill added that it is also vital that undefined microorganisms are not included in the definition. He noted, for example, that taking an extract of microbes from faecal samples and then heat inactivating them would not be considered a postbiotic according to the ISAPP consensus definition, “because the microbial biomass is not defined.”

“We think it has to be defined so that you can link it to the health benefit that you want to claim.”

Referring to the use of the term ‘inanimate’ in the definition, he noted that ISAPP specifically chose the word because it is not clearly understood and “makes people stop and think about it for a minute.”

“We wanted to avoid loaded terms like inactive, inert, killed, dead, as they could suggest ineffective,” he added – noting that such a decision was a nod to the commercial use of the term postbiotic.

“It would be difficult to say my postbiotic is made up of inactive bacteria that is then active in certain diseases,” he commented. “It would contain this kind of odd conundrum of how can something be inert or killed or dead, but still have an impact?”

Hill said there is lots of evidence to show inactivated or inanimate microbes can have an impact on the microbiome environment and human health. He cited a 2016 study that reviewed more than 50 studies from various strains showing benefits, adding that strains including Lactobacilli, Bifidobacteria, and Enterococcus have been shown to have effects in conditions including IBS, constipation, colitis, NAFLD, rhinitis and more.

However, he also added ISAPP also refers to ‘microorganisms’ very specifically, since the term is not limited to bacteria – and could also be used for yeasts, moulds, or fungi, for example.

The importance of ‘components’?

Hill said the ISAPP-convened experts made a very early decision to not re-define things that were already well defined by other terms, noting that if something is already has a term – for example a bacteriophage, bacteriocin, or butyrate or fermentate – then they do not need to be redefined or encompassed into the new postbiotic definition.

“A bacteriophage could be argued as something that appears after a bacterium is dead, because the bacteriophages killed it. But a bacteriophage is not a postbiotic, it’s a bacteriophage,” said Hill. “We don’t need new terms to replace old well defined terms.”

However, he noted that ISAPP did include the term ‘components’ in the definition because although a postbiotic must contain cell biomass from a microorganism, it might not contain intact microorganisms. Indeed, he noted that inactivation steps may also fragment or shatter cells. Postbiotics, however, must still contain microbial cell components like wall components, flagella, or pili said Hill.

“Cell biomass must be present, so even if organisms are not necessarily intact, the cell biomass must still be present,” he explained, noting that the definition contains some nuance relating to metabolites.

“The presence of microbial metabolites is anticipated in many postbiotic preparations, but the definition does not include those metabolites if they are purified away from their cellular biomass,” said Hill. “If you purify the metabolites, they’re no longer postbiotics, they’re metabolites,”

Hill cited butyric acid as an example of a metabolite that may be present in a postbiotic mixture but would not be classed as postbiotic itself if it was purified away from the cellular biomass.

Postboitics vs paraprobiotics: Not just semantics

According to Hill, the first challenge of the ISAPP process was to figure out whether postbiotics was the appropriate term to be defining, rather than, say paraprobiotics or ghost probiotics.

“We looked at the literature and we could see that between 2000 and 2019 there are quite a lot of papers that mentioned these different terms and in-fact he killed probiotics, was the most commonly used term in that 20 year period, and postbiotics is only the second most commonly used term,” said Hill.

“But if you look at the timeline of that you can see that for a long time term heat killed probiotics is being used quite a lot, but of late the term postbiotics really has taken over, and by 2019 it is the most dominant we used term,” he noted.

Another reason that postbiotics was preferred over terms like paraprobiotics or heat-killed probiotics is that these terms all rely on the use of the term probiotic, and the definition of a probiotic.

“[With these terms] it appears that something has to be a probiotic first and then it can become a paraprobiotic or heat-killed probiotic. We don’t think that is necessary. You do not have to be a probiotic in order to become a postbiotic,” Hill commented.